Oroville to Taylorsville – The Steady Grind

Mile 103.1 to Mile 194.6

From Oroville, the route turns northeast into the hills. It starts with a rolling 7-mile stretch to get to Interstate 70, climbs to Oroville Dam, then climbs further up to the town of Yankee Hill and over Jarbo Gap. From there, the road plunges (6-mile decent at 4% grade) into the Feather River Canyon. Once in the canyon, it is a long, slow, more or less unbroken ascent to the control in Taylorsville (elevation 3500′).

I rode this course a month earlier in the 600k brevet, and dreaded riding it again. At the same time, I knew what to expect. So when I reached the hills, I put the bike in low gear and took my time climbing. Even at that slower, more relaxed pace, I passed other riders on the way up. Which surprised me, because my bike is so heavy.

I should talk about my bike for a minute here.

The bike I rode was designed and built for me, for this ride, by my friend Rick Jorgensen. I cannot say enough about Rick, his understanding of bikes, and his skills. I also cannot say enough about the process of building this bike; it would just take too damned long. It was an incredible process. We talked about this bike, other bikes, cycling, randonnées, etc. pretty much every day for about 10 months. I cannot begin to capture that process here.

Rick designed this bike specifically for this ride, and no other. And more specifically, he designed it for the last 250 miles of this ride, and pretty much ignored what it needed to do for the first 500 miles. Rick was convinced I could do the first 500 miles on my carbon Ibis road bike if I had to, so that part of the ride did not really enter into the design parameters. Rick has a range of design philosophies. Two are relevant here.

The first is that in all designs, his goal is “to maximize the biomechanical interface between the human and the machine.†So he designed the bike as best as he knew how based on who I am, how I ride, and what ride I needed the bike for. In addition to our conversations, we rode together on various road and mountain bikes in a variety of terrains and conditions, all of which helped him understand how I ride.

Which leads to a second tenet: the weight of the bike is a result of good engineering, not a design parameter. So, for instance, my bike has front panniers. Their placement over the front wheel is the best place to carry load, and in this case, was designed to stabilize the bike’s steering as well, thereby decreasing my arm fatigue. But adding racks to hold the panniers adds weight. Some people will pay $40 or more for carbon fiber water bottle holders, rather than $10 for plastic, to save a few grams. We were adding pounds to the bike, not just grams. Rick’s contention is that a bike that fits well and does what it is designed to do will allow the rider to perform better; in any case, certainly better than a less well-designed bike that just happens to be lighter.

There is far more to discuss here, and I hope to discus the bike more fully elsewhere. But the point I’m trying to make is that as a result of going with front panniers, along with dozens of other decisions (such as carrying five water bottles, e.g.), my bike is pretty damned heavy.

So, as I was rolling along up these long grades, I was shocked to be passing other riders. What do you know? I thought. That crazy bastard Rick was right.

Another cool thing about this uphill stretch of road was that between my slow speed and the moon full up, I could ride with my headlight on low power. That allowed me to make sure my batteries would last all night. It also allowed me to look around and see more of the surrounding country. The moon was bright enough to cast my shadow on the pavement. I really didn’t need a headlight at all, but thought that if I crashed for some stupid reason, I would like to be able to say yes, the light was on. Besides, it helped the empty trucks bombing down the road toward me know I was there, for whatever that was worth.

Now, this light issue is another thing. Bike headlights are increasingly bright and efficient. They are also extremely lightweight, and as a result, there are more of them on each bike. Most riders have one or two mounted on the handlebars and another on their helmet. And they are all very bright LEDs, some with multiple bulbs. When you ride behind a group of riders at night, it looks like a UFO landing, like something out of The X-Files. When you ride in the group, it can be very uncomfortable. For while light is generally a good thing at night, too much can be bad.

For instance, if I am in front and the person behind me has their light on full, their light will cast my shadow in front of me, darkening the road. And there’s no reason for the bikes in back to have their lights on so bright anyway: when you’re following someone, all you are lighting is their butt and the reflective tape they’ve stuck all over their bike and helmet. The worst, though, are the people who run helmet lights on full all the time, because when someone with a helmet light turns to look at you, they blind you. Jonathan Grey, whom I rode with in the flats, had a helmet light; but he only turned it on when he needed to read a cue sheet to see what our next turn was. I wish all riders were that aware.

How did I get on this subject?

Low lighting. Right. I ride with my light as low as I comfortably can. And on this beautiful moonlit night, that was the lowest setting. Instead of fixating on the road, which was only passing by at 8mph anyway, I got to see the boulders and golden grass and green and tan oaks. I got to follow the folds of valleys fall away from the road. I got to do something other than focus on pavement and pedaling. It made the climbing a lot more enjoyable than it would otherwise have been. It’s times like this – riding by moonlight at 2am on a warm summer night – that make riding special.

After some time, I reached the top of Jarbo Gap. Time for the long decent. I caught up to a group of four of five riders just before the top. They were stopped, so I continued on past. I thought to ask what they were doing, but got too excited about going down to stop. And there’s that whole necessity to avoid unexpected stops thing, too. Anyway, I soon figured out what they were up to. They were putting on clothes. I had worked up a sweat coming up the hill. Now I was going downhill at about 30mph, and the air was getting colder with every 100 or so feet of decent. By the bottom, I was freezing.

And, in case anyone is concerned, I had the headlight on full for the decent. My friend Darell Dickey loaned me the light. In fact, he loaned it to me for the last six months. And it’s amazing. He was part of a team that designed this light, and it’s now sold out of Australia as a kit. Which isn’t all that important, really. Except that like the bike, which looked like no other on this ride, the light looked like no other. It has three LEDs in a huge casing with an immense heat sink that kind of looks like a miniature Robbie the Robot out of Forbidden Planet. Darell modified it for me to run off 12 AA batteries so I could replace them anywhere on the road without having to find an outlet to recharge a battery pack. He also set the maximum brightness to ¾ of its full potential (750mA). And still, when I turned the light up, I could, as someone else once said, fry road kill at 20 yards. Point is, it’s a bright fucking light. I couldn’t outrun its beam even later in the ride when I was topping 40mph down steeper hills.

So, I’m flying downhill, light on full, starting to shiver, and trying not to get distracted by the grandeur of the canyon I was dropping into. This is one of those times when I think, Why don’t I stop and enjoy some of the scenery? I have that thought a lot while riding, and like my time-speed-distance calculations, it’s one of those topics of internal debate that never gets settled. I still don’t know why I didn’t stop, because soon I was crossing the bridge and sailing along the canyon just above the river. A few miles later I finally got so cold that I did stop and put my vest on. There was a road maintenance yard that was lit, and two other riders were there. Far less scenic than the descent into the canyon. But what the hell. I guess I just got uncomfortable enough.

Not long after, I pulled into Tobin control. Tobin is a tiny set of resort cabins halfway up the canyon between Oroville and Taylorsville. It has a post office and a lodge. I arrived about 4:50am. The folks running the control had strung christmas lights out front. Bikes – expensive bikes – were strewn all around, lying in the dirt lot. It was strange to see them, each worth thousands of dollars, lying all around. The control was in the lodge which had a low wood ceiling. It was cozy, and warm, and reminded me of a train dining car. A huge selection of food was laid out all along one counter.

I don’t remember what I ate there. But I do recall being worried about falling sleep while riding after the sun rose, so I took a 30-minute nap. The club had rented a number of cabins, so I took my shoes off and lay under the covers for a very welcome power nap. I was rolling again in less than an hour, feeling rested and ready for the next tedious stretch.

The next official stop was Taylorsville. To get there, the route turns off Interstate 70 and heads north on Highway 89. After a steep climb, the road enters Indian Valley, an area northwest of the Feather River Canyon and on the way to Lake Almanor. This is a beautiful little corner of the world, and someplace I would never have known about but for riding. There is a cutoff at the lower end of the valley to go directly to Taylorsville. But our outbound route passes this cutoff, and for better or worse, circles the entire valley and heads up to Greenville in the northwest corner before turning east to get to Taylorsville.

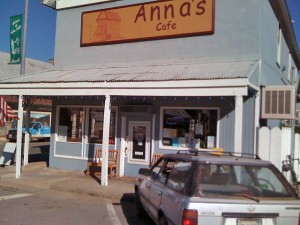

On this road for the 600k, I remembered thinking I should stop in Greenville first to eat breakfast. It was a kind of promise I made to myself that if I rode though the town again, I’d at least stop long enough to eat. I think it’s a mistake to charge through these areas without spending a little time, even though I keep doing it. So I planned to stop at Anna’s on the corner of Highway 89 and Main to have breakfast.

Just before entering Greenville, I caught up to fellow DBCer Paul Gutenberg. Paul was, as always, talking – this time to his riding companion, Nicole. I recognized his riding style and outfit from a quarter mile back, and started hearing him from about 100 yards off. I only mention this because from the start, I was wondering when I would catch up to Paul. In each of the previous brevets this season – 200k, 300k, 400k, and 600k – I had at some point in the ride caught up to him and in most cases rode with him the rest of the way. For this ride, especially with my having to retrace the first part of the course, I took catching up to him as a sign that I was back on schedule.

And there is something reassuring about the consistency of Paul. Knowing I would catch up at some point, that he would be wearing a helmet with red on the back and a day-glo green shell that puffed up like the Michelin Man, and that he’d be talking in that happy baritone voice of his . . . all of that somehow told me all was right and as it should be.

So I rode with Paul and Nicole the last few miles into Greenville. And in the first test of sticking to my plan, I stopped for breakfast while they continued on to Taylorsville 12 miles on.

I can’t say breakfast at Anna’s was especially noteworthy. But it was nice to have a breakfast burrito and talk to a few people in the restaurant there and be sort of an ambassador – explaining why all the cyclists were coming through and where we were headed. It was, as I had hoped, a little bit of a grounding experience – a chance to step out of the cycling reality for a while and to come back to the ride a little fresher. Leaving the restaurant and riding slowly away in the morning sun, I felt more like I had just had breakfast after a 30-mile ride rather than the 180-mile ride I actually had under my belt.

From Greenville, the road to Taylorsville along the northern edge of Indian Valley is mostly flat with just small rollers to slow you down and speed you up again. This was a fun stretch, a carefree stretch of road. I came into Taylorsville feeling rested, well-fed, and very strong.

The crew at Taylorsville control was incredible. They were cooking breakfast to order in a tiny kitchen: eggs, meat, pancakes, french toast. I had just eaten, so I passed. In retrospect that was a mistake. But at the time, I wanted to move on. I had just spent an extra 40 minutes in Greenville. I stayed long enough to restock water bottles and visit a little with John Hess, who was working at Taylersville control.

John had asked me before the ride if there was anything I would want at this stop. I’d said espresso. John understands these things. A couple of years earlier, we were both on the Davis Bike Club’s San Juan Islands tour. He’d brought Peets coffee and brewed enough every morning for anyone on the tour who had wanted some. He and his wife, Katherine, had researched every decent coffee house and brew pub on our trip, and their daily bike rides were largely between these destinations. These people know how to travel. So John dutifully packed up his compact home espresso machine, a set of demitasse cups he found at the SPCA thrift store, and a couple of pounds of Peets. Once I was done getting my possibles, and without having to ask, he handed me a double espresso. And think about it: how many people would be sensitive enough to serve espresso in a demitasse cup? I was so touched by this generosity that I felt a little choked up. I thanked him and got going again.